By Bishop Maxim (Vasiljević)

Stamatis Skliris’ contribution to modern art (both Church art, and art in general) through his painting and iconography is already a generally established fact. With this review we would like to sketch the historical context behind the appearance of Skliris the zographos (i.e. one who paints from life or from nature using fresh, natural colors) and, by making a theological-aesthetical analysis of his iconographic opus, to emphasize clearly and objectively some of the particular qualities of his art in relation to the iconography of the second half of the twentieth century.

1. Iconography of the first half of the twentieth century. During the first half of the twentieth century, Greek iconography was briefly dominated by lay tendencies. There existed an authentic lay tradition, e.g., Theophilos. After Theophilos, the lay tradition ended once and for all because the artist became a learned man, a logios. Already from the first half of the twentieth century, Photios Kontoglou initiated an attempt to merge lay tradition and the “learned” art of painting. He went to Paris in 1921, where he got into the general tendencies of the Romantics and their investigation of local traditions. He returned to Greece in this spirit and became inspired first by the monasteries of Meteora, and then by Cretan iconographers and lay painters (see the collection of articles on Kontoglou entitled Ἄνθρωπος ἐν εἰκόνι διαπορεύεται, published by Akritas, as well as the text on Kontoglou by Nikos Zias).

The first half of the twentieth century was marked by the anasynthesis of neo-Greek society, which after the liberation from the Turks was again subjected to many Western influences due to Bavarian rule; and these influences ran parallel to Byzantine tradition. This anasynthesis occurred mainly due to Kontoglou, and later to Pelekasi. Kontoglou linked lay and post-Byzantine traditions, while Pelekasi established links with the traditional art of Eptanisa (the Seven Islands of Greece), which belonged to the Greek traditional mainstream but also contained a multitude of Baroque and Renaissance elements. Accordingly, the roles of Asia Minor and Kontoglou (he was from Kydonai in Asia Minor) were very significant. However, the geographical and cultural environment within which Kontoglou was active was Athens. This proved to be the geographical and cultural setting from which arose the seminal activities and tendencies that characterize present-day Church iconography. Kontoglou did not bring along with him any concrete tradition from Asia Minor, but he brought a spirit of preserving tradition and of protecting dogmas by means of the icon. Greece had a very concrete and very well-developed lay and Church iconography. Kontoglou had the traditional spirit, and Greece presented him with the icons of Meteora, the Holy Mountain, Panagiotes Zographos, and Theophilos, the last surviving lay painter of Kontoglou’s time.

The first generation of Kontoglou’s students turned to an older phase in the development of Byzantine painting as compared to the one which influenced Kontoglou. Spyros Papanicolaou was inspired by twelfth-century Castoria, Peter Vampoulis by the fourteenth-century Monastery of Chora, and Yannis Karusos by the Monastery of Sopochani in Serbia (1260–1265). Later on, the second generation, and especially Dimitrios Tsiantas, was inspired by Michael Astrapa, Euthychios and Panselinos (end of the thirteenth and beginning of the fourteenth centuries). Kontoglou was not partial toward these periods of Byzantine art, being under the impression that they were worldly, but he was greatly attracted to late Byzantine and lay art. It was his students who turned toward integral Byzantine forms. Kontoglou himself offered the wrong criteria for the evaluation of Byzantine art. He emphasised the element of tenderness (katanixeos) and dark colors, while Byzantium had light colors and emphasized doxological and eschatological elements. (The Brothers Lepur, for example, desired to be Kontoglou’s students by their own free will, but they expressed a more lay articulation.)

Since Kontoglou’s death, there has existed yet another generation of his students, who have gone beyond the problems relating to post-Byzantine and Byzantine art, between “doxologizing” and “tenderness.” The exaggerated influence of the great teacher was abrogated, but they kept from him one other element which their predecessors did not utilize, and this was the fact that Kontoglou painted worldly themes employing Byzantine style and techniques. Thus they managed to open themselves to a new comprehension which connected worldly art with Church art, which did not differentiate between a saint and a worldly man. This used to be an unyielding rule of Byzantine art. It was Kontoglou who reintroduced this spirit into more recent times, especially when painting Greek history on the walls of the great assembly room of the Parliament in Athens. Thessalonica’s John Vranos continued in this spirit (with comic elements), as did Yorgos Kordis (with elements of Cretan iconography), Spyros Kardamakis (Cretan and lay elements), Manolis Grigoreas (with his simple, childlike drawings), and Fr. Stamatis Skliris (with elements of a more Palaeologan art of painting).

In our day and age, when a renaissance of Church art is to be seen in all Orthodox countries and nations, Athens still manages to retain a uniqueness throughout the world, which history will know as the School of Athens. The majority of iconographers in Serbia copy Astrapa. This is the form that this renaissance of Church art is taking in Serbia. In Russia it takes the form of a return to more ancient sources such as that of Sinai (sixth to twelfth centuries): Hieromonk Xeno. Thessalonica is deeply immersed in research into Palaeologan and Cretan icons, which have been preserved on the Holy Mountain. Copies of Theophanes the Cretan (sixteenth century) are made in almost all Greek monasteries. Only Athens has a grand workshop which is being ceaselessly inundated with ideas, where new tendencies are constantly emerging, where a leavening occurs on a daily basis, and where the artwork of one artist is being discussed in relation to the artwork of another (Karusos-Leondas, Tsiantas-Vlachoyanis, Yorgos Kopsidas, Sideris, Kardamakis, Kordis, Manolis Grigoreas, Stamatis Skliris). All this is still in a state of development, and it is still too early for any conclusions to be made.

2. Special elements of Stamatis Skliris’ iconography. Special characteristics of the painting of Stamatis Skliris are the following:

a) He ascends from the very beginnings of iconography (catacombs, Dura Europos, Sinai, etc.) and from classical Hellenic presumptions of iconography, striving to revitalize the initial solutions and choices made by early Christian art. Rather than following the ready-made mannerisms which were formed throughout the centuries, he chooses to observe the very first choices (for example, his works: St. Catherine, p. 49; Annunciation, p. 71; Caryatid with a Seashell, p. 97; Kouros, p. 99; Alexander, p. 99). [The paintings are listed according to the page numbers in Stamatis Skliris’s book: У огледалу и загонетки (In the Mirror and the Enigma), Belgrade, 2005.]

b) He adopts elements of Persian, Hindu and Turkish miniatures, and “borrows in return”: Anatolians borrowed from Byzantium, and Stamatis borrows from the borrower (painting: The Primitives, pp. 292, 295).

c) He articulates a dialogue with modern art by evaluating the brush strokes of Van Gogh and Cézanne, Monet’s colors, Matisse’s forms, Picasso’s Cubism, and Post-modernism (paintings: Melchizedek, Resurrection of the Son of the Widow of Sarep, pp. 498 and 270–71).

d) He is authentically post-modern, because he employs purely artistic criteria; he does not adopt ready-made solutions from the iconographic past; he researches everything anew; a strong experimental sense is at his disposal, and he combines strictly traditional elements with those that are modern; e.g., The Mighty Protectress (Theotokos) is strongly traditional, but Christ has the movement, the colors, and brush deposits of modern, expressionist art (title page and p. 39).

e) Light plays the most significant role; it is Byzantine, but Stamatis looks at it in a neo-impressionist manner, i.e., he captures Byzantine light with brush strokes that emphasize dominant points in an impressionist manner.

f) He uses strong and clear color, avoiding mixtures of different colors (painting: Apostle Paul, p. 403).

g) His colors and drawings relate to us a beauty and a joy of a modern type, which theologically expresses eschatological tranquility rather than Kontoglou’s tenderness or penitence (painting: The Mansards, p. 157).

h) He gives anew to the elements of nature some of their basic characteristics which were neglected by Cretan painting and presented only symbolically. For example, water has a freshness and dynamic wave agitation rather than nicely combed waves (frescos and icons: Ascension of Prophet Elijah, Elder Zosima Gives Communion to Mary of Egypt, p. 179).

i) Although he basically employs a dark Byzantine underpainting, adding to it light “accents” (illuminations), he still plays with colors in such an impressionist manner that his work gains a “non-determinism of color”; he leaves sections of his painting uncolored and then treats these sections in an unpredictable manner with an eagerness to play and not to make use of the calligraphy that is usual in iconography (painting: Transfiguration, pp. 149, 151).

j) In spite of the strong eschatological dimension of his work, he allows for a somewhat dispersed manifestation of tragic and psychological elements, which puts him in line with twentieth-century painters (painting: Nightmare, p. 245).

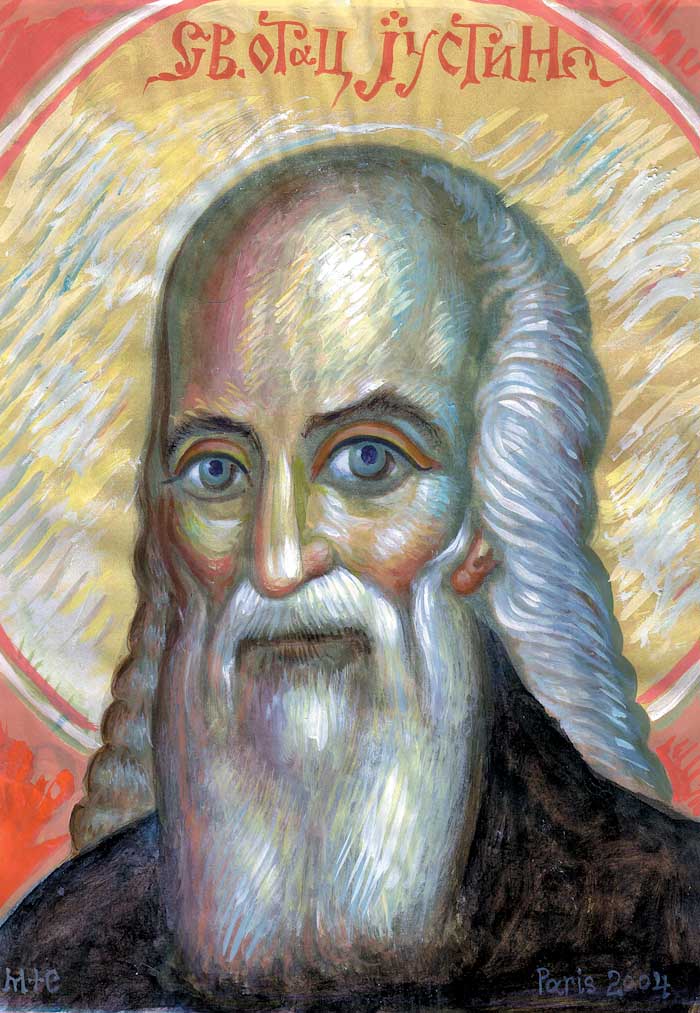

k) Most characteristic of all is the strong portrait dimension which marks his icons, as well as the fact that he introduces into church interiors a contemporary facial expression (paintings: St. Thomas and St. Dimitrios, in the church of Prophet Elijah in Piraeus, pp. 501, 397).

l) The look in the eyes is not only transcendent, as is the case with old icons, but it also has some special features which are applicable to modern man: (i) an intense look; (ii) a look which creates a relationship with the observer-pilgrim; (iii) a psychological look; (iv) a look that thinks and examines (paintings: The Tree-Woman, The Thinking Girl, p. 98).

Upon observing Stamatis’ artwork, we see that he manages to link the graphic and the chromatic elements both harmoniously and with rare originality, thus anticipating with his drawing and coloring a wondrous world, God’s world of love and light. With regard to the graphic element, by the mobility and expressiveness of his images, with the open, childlike looks in their eyes—through his excellent knowledge of anatomy (being a medical doctor) and of psychology (being a priest and a spiritual father)—Stamatis overcomes the immobility and inertia of fallen human nature through a movement of reaching out, which is the feat of loving and of an eager progress toward Christ. As far as coloration is concerned, by a combination of color (warm-cold, complementary), by a gradation of tones, and by a multitude of vibrating shades brought on by the brush—employing the best solutions from the history of the art of painting (Byzantine, impressionist, cubistic, abstract, surrealist, etc.)—and in doing all this, illuminating everything by light, Stamatis anticipates the coloration of Paradise, the coloration of “a new Heaven and a new Earth” (Rev. 21:1). In addition to this, he also offers a thematic contribution: he does not overlook emphasizing the historic, tragic element (agony, suffering, wounds, and pain) in the images of saints and martyrs depicted in his works, and especially in his most recent creations, which are, nevertheless, illuminated by the Light which overcomes the world and history.

(Translated from the original Serbian text by Petar V. Sherovich)